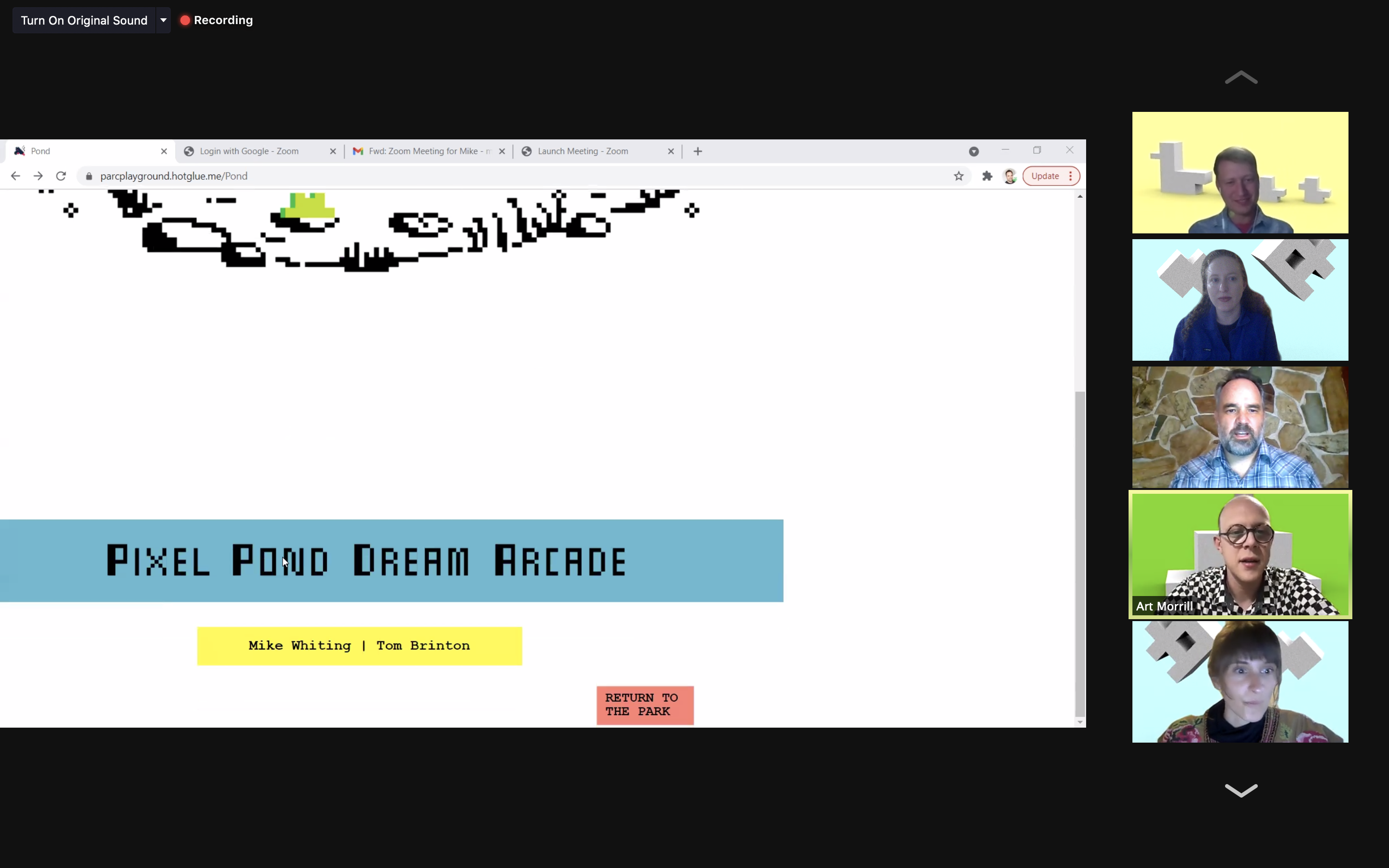

AN EVENING IN THE PIXEL POND DREAM ARCADE

A discussion with Mike Whiting

Edited Transcript

May 7, 2021

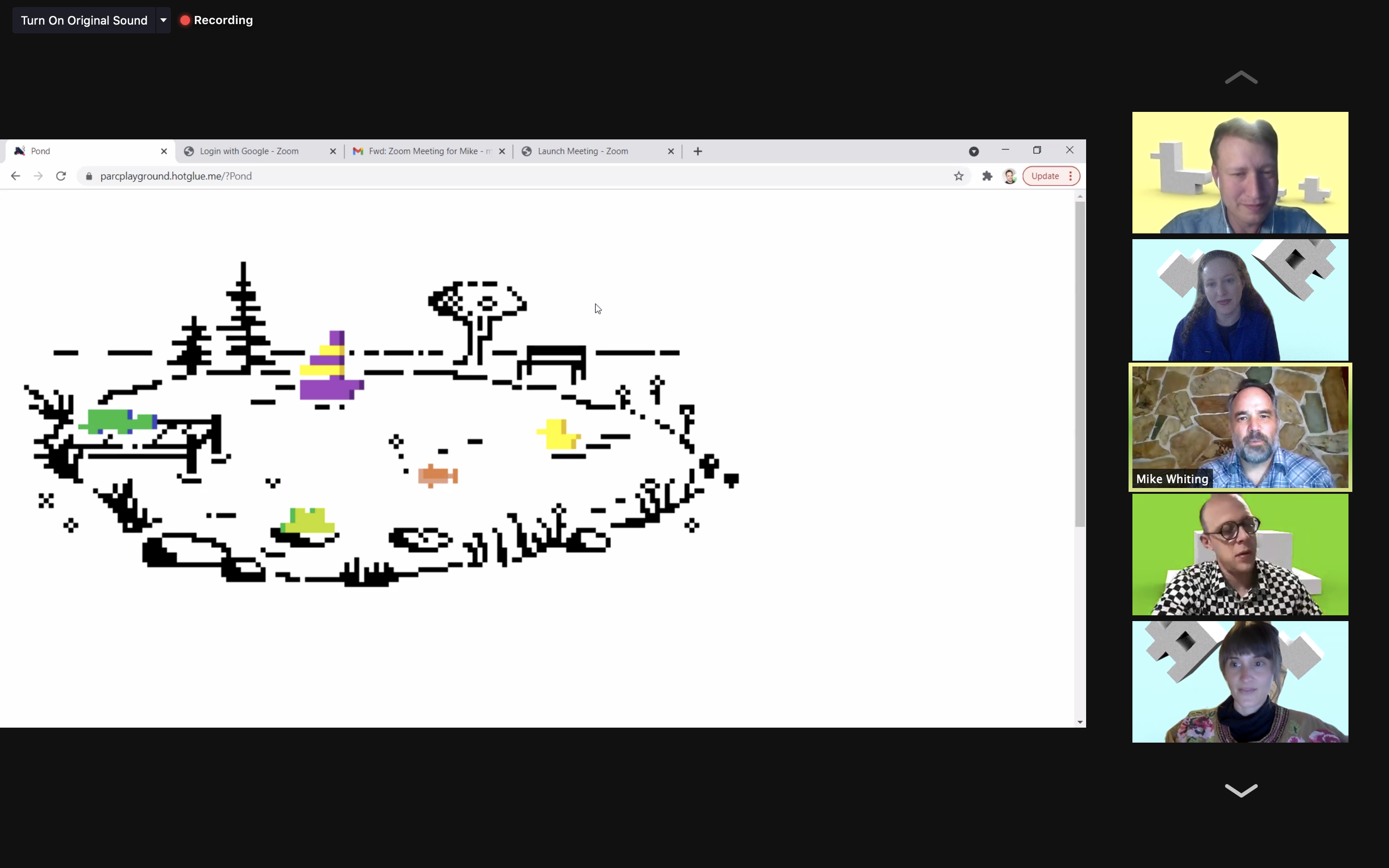

Mike: So when I started [this work], I was all over the place with ideas; I was trying to figure out how to make [this format] work with the way that I normally work. And I do draw, I use the computer and 3d modeling programs to come up with proposals. So eventually I came to think of this space as an actual park, and what would I actually propose and what kind of models would I draw for that.

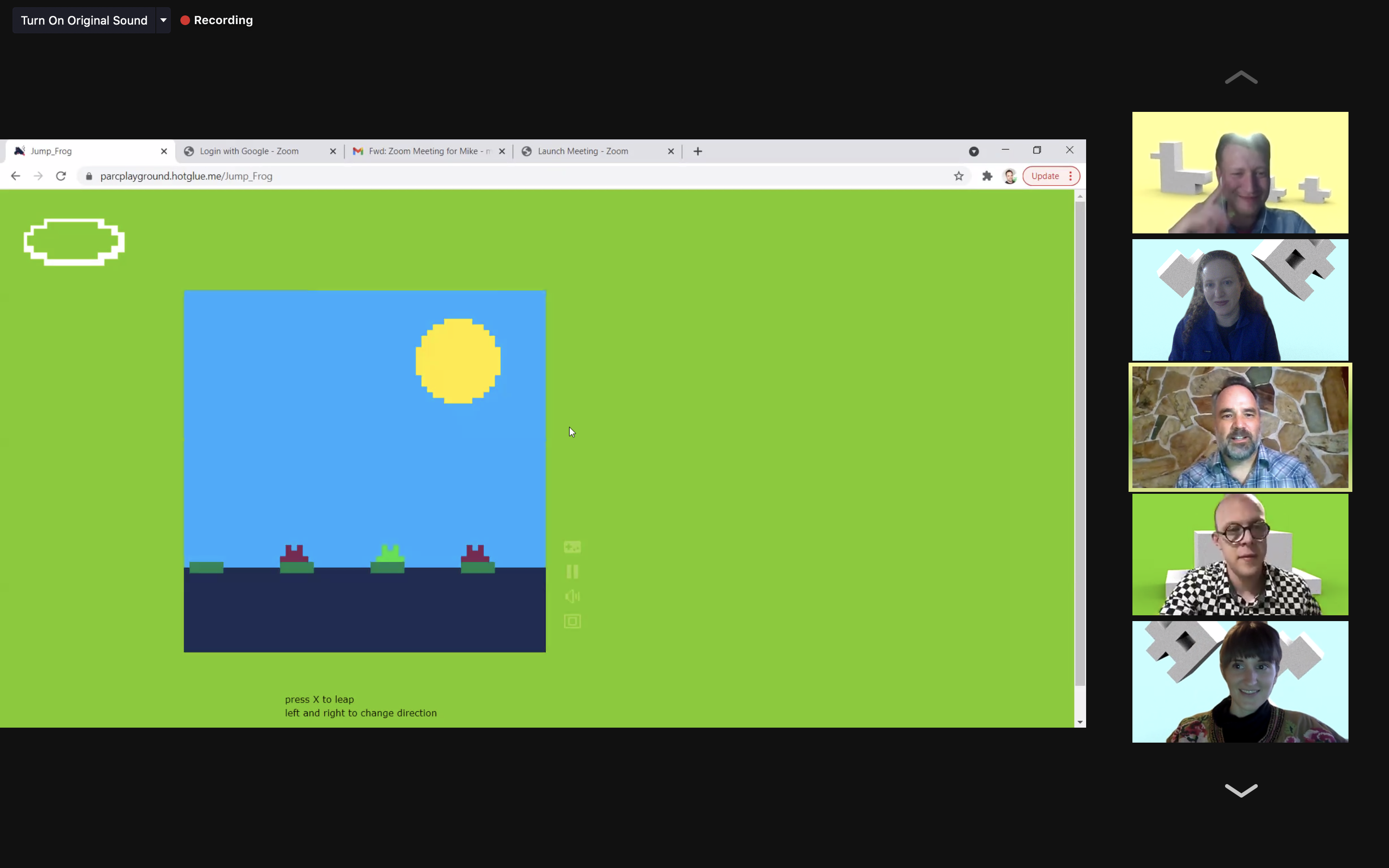

FROGS

Mike: We'll start with the frog. I think that's the first game that Tom and I came up with.

I draw with Microsoft Paint one pixel at a time. And from there I translate that into a 3d modeling program and I can figure out the depth and all the parts that I need to make a sculpture. These [3D images] are the images that usually come out of that. Normally I'd color the image in, and the background would be white. I’m doing something a little different here.

When you click on the frog, it takes you to our game. We're here with Tom Brinton, and we came up with these together. I've wanted to make a video game forever! I used to collect Atari cartridges and stuff, and I’ve looked into ways to program an Atari game and it was very complicated--but apparently [programming] has come a long way, and plus Tom really knows what he’s doing here. These [games] have very simple directions: you can change direction and jump; you can change directions and go back the other way. And there's no end to these [games,] it's just a loop.

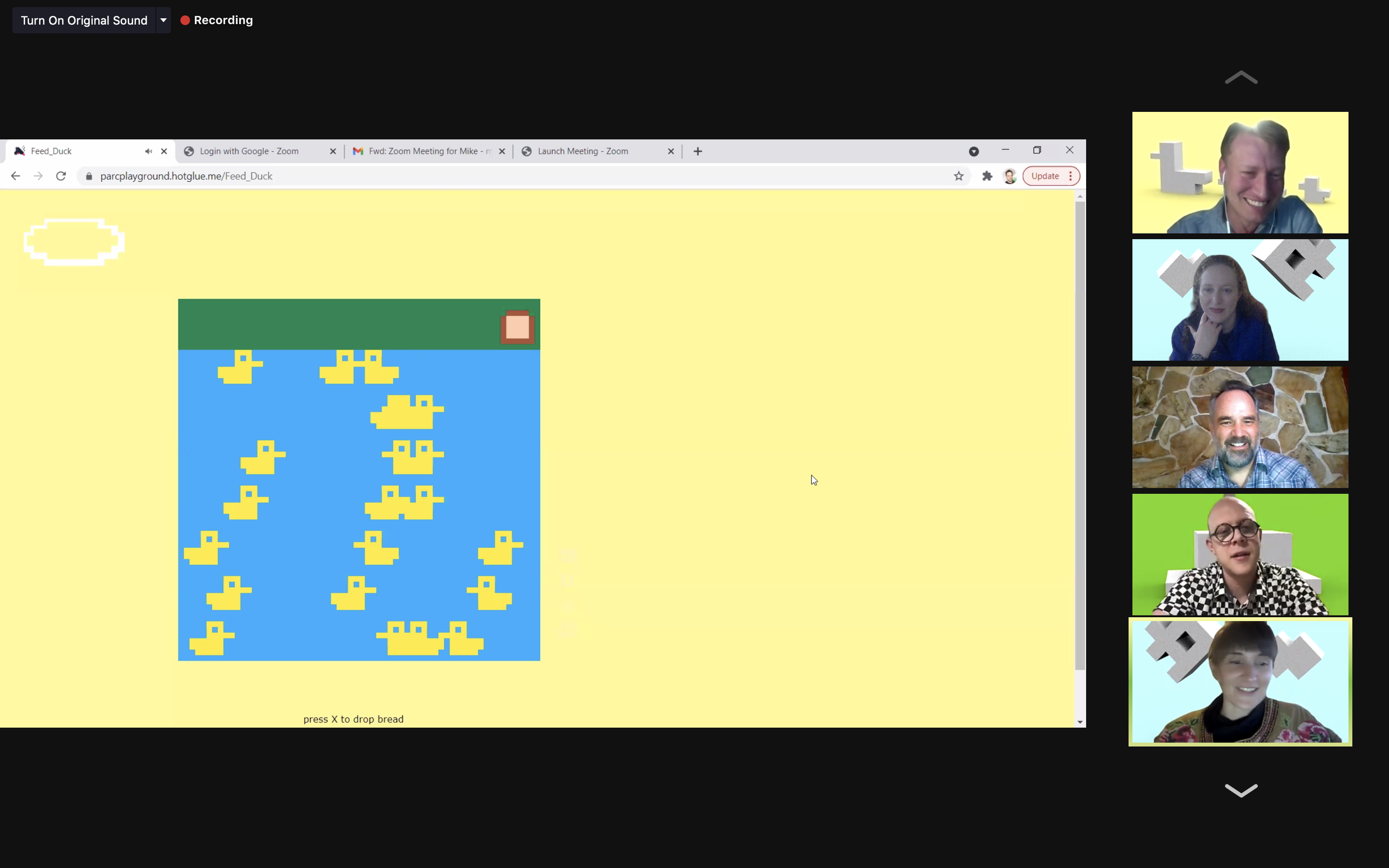

DUCKS

Mike: I've actually made these ducks in real life before. I made these little ducks several times, and one of these larger versions too. This game that we came up with is something I had in my mind--I could see the game but I had no idea how to make it happen. And the game that we came up with that Tom made is exactly what I had pictured. This is actually my favorite one. You got the bread at the top and a duck, swimming, back and forth. You can move the bread to get ready to drop it to the duck.

Tiana: I've always been really bad at these games where you have to time things, when things are moving in opposite directions.

Mike: But it gets easier--every time one duck gets bread he tells a friend that there's bread over here. It's like something that would happen at a park--you start feeding one bird, and then pretty soon you regret feeding that one bird.

Ron: With this one, like at least for me, the objective changed halfway through; I started to try to drop the bread and see if it could get all the way through [without being eaten by a duck].

Tiana: I did the same thing! I was looking for the holes and the negative space to see if I could get the bread down to the bottom duck. The duck that was furthest away from the bread felt neglected.

Ron: Yeah, these ducks up at the top get all the best bread.

….

Art: One of the interesting aspects of these games is that they don't have a clear objective, they're all kind of open-ended.

Mike: That’s true. In a way, I was thinking about how when you go to the park, you don't really have a clear objective. When you go to the park you’re there to hang out and, you know, feed the birds.

Art: That’s interesting because then, in a way, [the game] actually becomes more true to life than a traditional arcade-style game. Ron posed this great question about lacking an objective: do you think that the lack of an objective makes this [work] inherently more “art,” like an art piece, as opposed to a game?

Mike: In some ways, yeah probably. But at the same time I think art sometimes has objectives, it's trying to do something. It’s an interesting question. I don't know if I have an answer to that one. But yes, when I was thinking about these games, I didn't want them to be hyper competitive or addictive, like many video games are these days. I wanted it to be more of a casual experience, one where you don't really have to have skill. I think the turtle game is the one that requires the most skill. And the games are a little bit absurd--I mean the duck [game] is kind of silly. There's a little bit of comedy in the fact that you can't really “win” the game. There’s a limit to what you can do.

Art: I like that idea of comedy--I feel like one of the endearing parts of your work is that there’s always a certain amount of comedy involved.

Mike: There is, and I've actually gotten yelled at by other artists saying that I wasn't serious, you know, that the art has to be serious and you can't be funny or silly when you're making something. But the things I build are serious--you have to really put some effort into building these giant structures. So the [physical] work is a serious [labor], but I don't know that the subject matter has to be serious to be art. But yes, more than once I've been told that my work was not taking itself seriously.

Art: That's an interesting thought, this idea of being serious. If I relate it to some other giant iconic steel sculptures like a Richard Serra--there’s this looming doom involved with his work.

Your work kind of refutes that even though it's just as heavy or just as [physically] imposing.

Mike: That's a very good example of serious [art], it's as serious as it gets with Richard Serra.

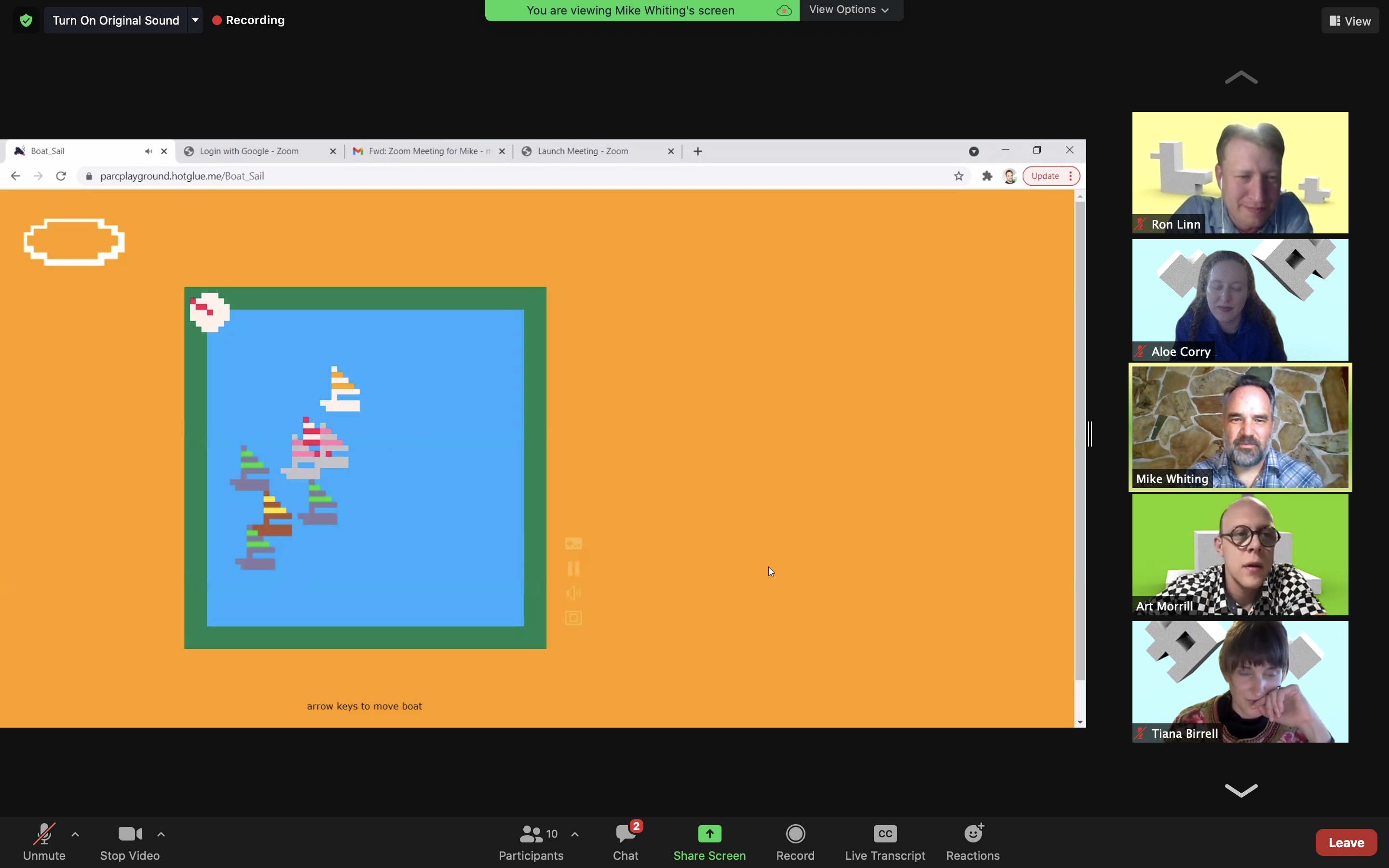

BOATS

Mike: So [these images] I have actually built [physically]. These [images] are from a real life sculpture; I built a sailboat in Denver, in the Botanic Gardens. It was actually in the water in the children's section of the park, and it was the same color of orange [as the background]. It had orange stripes and white stripes.

[And in this game] you're that boat. You use arrow keys--Tom came up with this idea of the wind pushing all the boats, and so when you play the game you can kind of move against the wind a little bit. There's a bit of resistance--the other boats are kind of getting pushed around. Again, there’s the idea of being at the park; the green [border] is the limit of the pond. You can only do so much, you're not sailing across an ocean or anything--its a limited space.

Aloe: With this game, I found myself drifting along with the boats. There's a feeling of bouncing around in that square and I think, as Albert mentioned [in the comments], it feels very meditative. I don't know if that's the counterpoint to addiction--there is a lure, right? I become mesmerized [by the boats]. One thing that I've been wondering about: you've been working with these really big, heavy, very physical objects that take their original inspiration from pixels. And now you've put your work back into that pixel world. How has that process been?

Mike: It's been super fun. I think you have some good points there--this idea of this [work] being more meditative than than the normal video game. [As a player] you’re really concerned with doing everything exactly right, [instead] you can get into the groove of it. And it’s exciting that you can move these things [in the game]. Normally for one of my sculptures you would need a crane. For these images, you just need your fingers and you can move this thing around with little arrow keys, it's totally different. [The shapes] become interactive by [the player] moving them around--whereas with my [original] sculptures, you interact with one by moving around it. It’s completely different.

That's where the title [Pixel Pond Dream Arcade] comes from--in a previous conversation we were talking about this idea of these sculptural images. The [original] sculptures are not able to move. These games are possibly their dreams of being able to move around freely.

Aloe: I think one of the fun parts about this work is that you give enough space for people to make their own narratives, but also to let it be just what it is--a simple action, a repetitive action. It’s been really fun to me to experience that lightness of your work moving, [my fingers] being able to push these things which I might have previously thought of as huge. The weight feels so different.

Mike: The other thing that surprised me [when making these games] was how much these images become moving paintings. As the boats change and move around in this game, the composition changes.

Tiana: I appreciate that when the boats themselves start to collide, they don't capsize--they kind of make these new different pixel shapes.

Mike: Yeah, they're interesting! I think the game generates different boats every time you go in to play, which is fun.

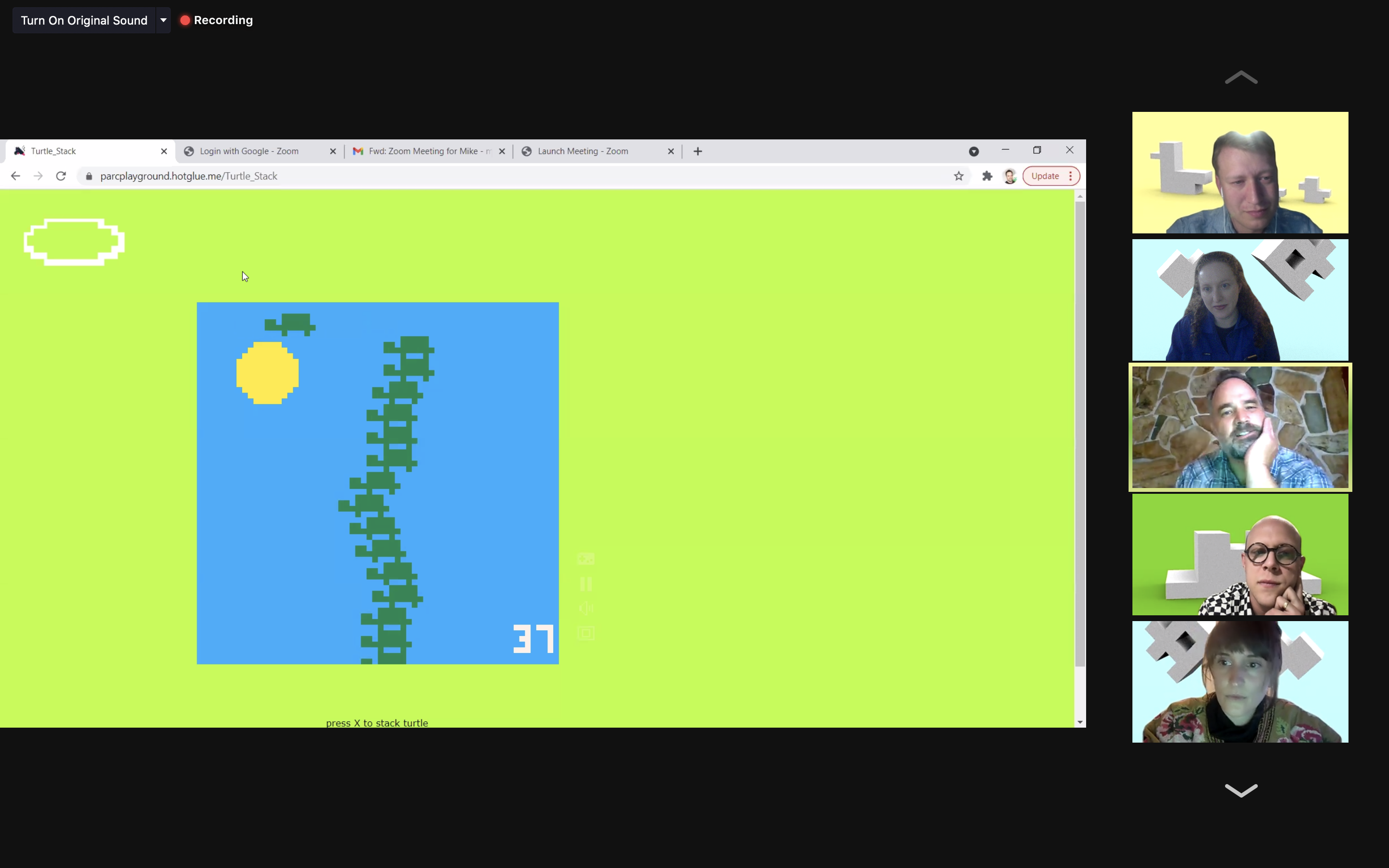

TURTLE STACK

Mike: Tiana, What was your record again?

Tiana: 30 turtles.

Aloe: I only got to 14!

Mike: I've never made a turtle sculpture; I think I’m going to have to after this. The aim of the game is to make the turtles stack [on top of each other].

Art: you mentioned earlier that you’d wanted to make games for a while.

Mike: Yeah, for a long time.

Art: Now that you have this body of work, of games, how does that influence how you look at your sculptures? Do you feel [this process] is going to influence your sculptures in the future, now that you've realized this dream?

Mike: It's definitely opened up a new thing. I do hope to collaborate with Tom more and make some more of these games, maybe go a little more in depth. I don't know if I've had enough time to process it yet. It'll be interesting to see how [making these] changes things. I don't know the answer to that question yet.

Tiana: The weight [of the objects] becomes really apparent in this game. You're playing with balance and gravity, but also stacking and tessellations. I’ve been thinking about your physical sculptures and how much labor goes into making them, moving them, and getting them approved for their [locations]. I'm sure you have to consider whether your object is dangerous to stand by. When I think about standing by this piece, iit would feel seriously playful and scary--to be under this looming stack of turtles. I’m curious about how weight will play into your physical pieces in the future.

Mike: I am too. This [process] opened up some new ideas and new territory.

Ron: As I was playing this game, I thought of the saying “turtles all the way down.” I’m thinking about your work in relation to environment building, and how [your artworks] make viewers more aware of their environment. We've been talking a lot about that in this game--if you mistimed a turtle [while stacking] in real life, it would be terrifying. But even with your physical sculptures--they're so imposing, but they’re also so playful and [when you encounter them] it's almost like there's like a glitch in the real world and it suddenly peels back and you realize you're in a game or a simulation.

Mike: When I do public projects I think a lot about place-building, creating a sense of place, something unique to that area--if it's just a place marker or if [the sculpture] is incorporated into the space. So I think about that a lot in my public work. But even in my smaller scale works it's even more apparent. This space between the virtual and real starts to shift; these pixelated things start to occupy our space.

That's what really fascinated me about your PARC Park project--this idea of taking a park and making it virtual. I’ve been working with making virtual things and putting them in the real world. You guys took the real world, put it in the virtual world. And now I've got to kind of respond to that world. And as far as place-building [in that world] I got to do that more with this project. I'm usually not in charge of where a sculpture goes. I just respond to the [given] environment. For this project...I got to imagine where all these works lived in a virtual environment.

Art: These works achieve one of our goals in building PARC Park, which was to build community, I don't think we ever quite imagined that you would make actual games out of your work and take this kind of community opportunity to a whole new level, where people can come and actually really play in the park.

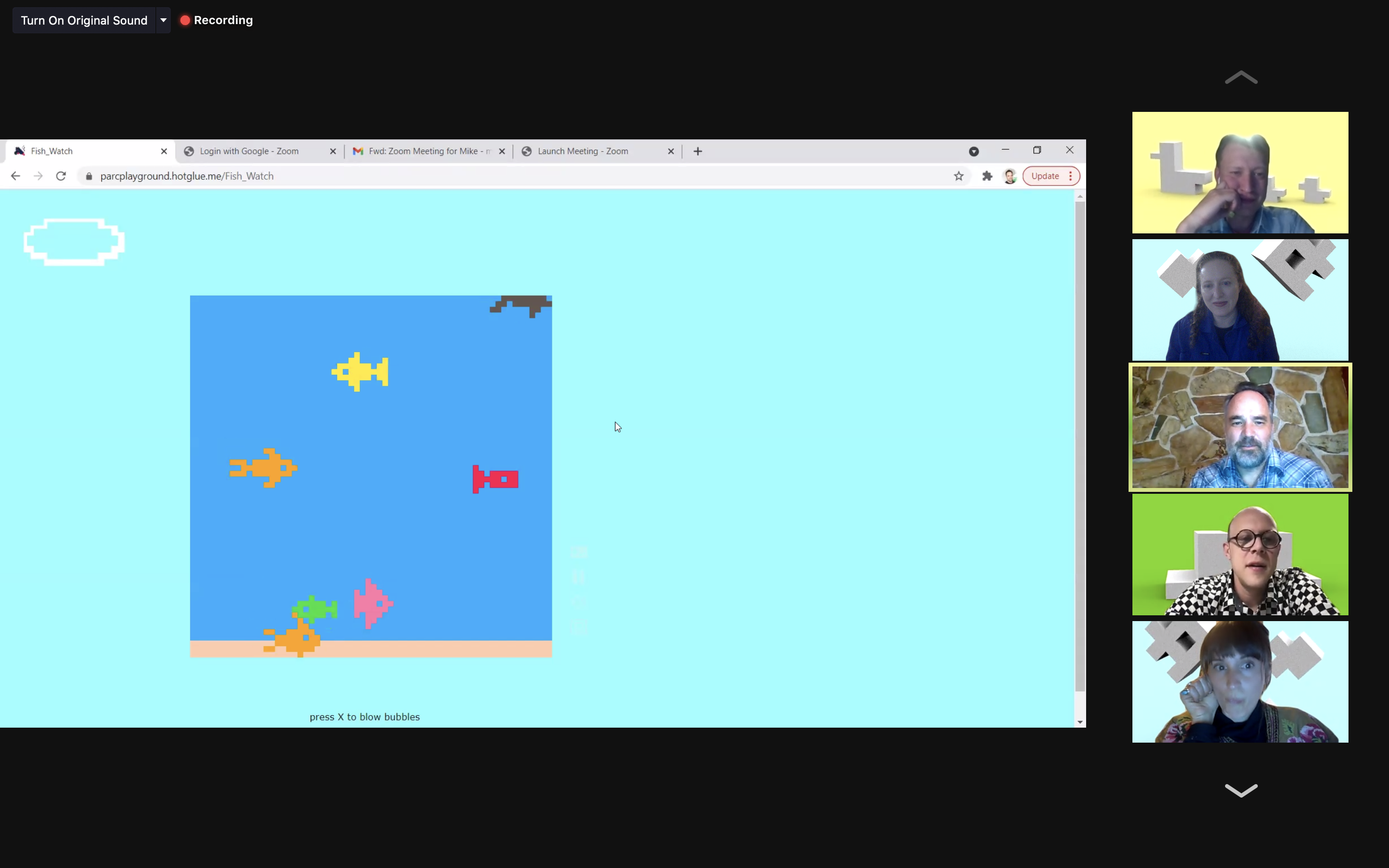

FISH

Mike: When I chose to work in the pond I knew I wanted fish in there somehow. I came up with some of [games that] were very complicated. Tom was good about helping me come back down from what was too complicated to program. We started on the same page, but we really get on the same page towards the end [of our collaboration]. It's been great.

For this game we wanted something that was interactive, but not too interactive. So we came up with players pressing X to have the fish blow bubbles. That's all you can do in this game, really, and that's kind of all you can do at a reas park--just kind of watch what's there.I think this piece really works well as a changing composition like a painting where these things are moving around.

Aloe: It makes me ask myself if I’m looking at it like a fish tank, or if I’m looking at the fish from above. I go back and forth between the two, which is really fun.

Ron: This is one of the games for me that really resists an objective or goal--[in the other games] you can stack the turtles, you challenge yourself with the bread and the ducks, but with this one and the boat game, you're just interacting with the images--kind of like you might interact in life.

Tiana: The fish feel very Corey Archangel-like; I don’t know if you've seen his Super Mario clouds piece, where the clouds just kind of scroll by. It's a very similar blue to [the water pictured] here. There's something really satisfying about making an homage to Atari or earlier video games--how a simple color can draw lines between things.

Mike: That was one of the things we had to work with; there's so many colors you can work with in the [game-building] program.

Tom. These games were built in something called PICO-8, which is a fantasy console. it's like an imaginary game console that never existed except as a software. The limitations are all artificial really, but they’re there to give you that creative constraint. There's a palette of 16 colors, just like a lot of old consoles and computers had. The screen size is also 64 by 64 pixels in this mode; it forces you to think differently when you don't have the full power of your computer to work with. Instead [the program] lets you take a small piece of processing power and let you play within it.

Mike: That's how I work when I make my [physical] pieces. I like the idea of putting really strict parameters on what you can do and then trying to work within that. It pushes a different kind of creativity; you have to figure out how to work in a really small, restricted set of rules. That's why I often will paint like a deer orange instead of brown--it references these kinds of colors that people see in earlier video games.

Aloe: That was something that I was curious about. You've been talking about your games as “painterly,” as canvases or limited areas. I find myself wondering how you managed your color choices. Were you going towards trying to capture a specific time or feeling, or really trying to take advantage of that 16 color palette.

Mike: Like Tom said, we were very limited. There were only two kinds of blue to use--this [bright] blue and a very dark blue. Trying to have a different color for water and a different color for a sky became a challenge. And there's something really nice about that, how the colors capture an era, just because of that [engineered] lack of technology. Those old Atari games are very, very limited. And that speaks to this whole idea that I've been working with for a long time-- looking at these older movements: pixelated images or going further back to proto-minimalism, where [images] were very purposefully reduced. They were trying to get to the essence of something. Early technologies were forced to work within the essence of the smallest image they could make, they got down to a square. That's really the building block of so many things.

Tom: In video games, especially 2d video games, these little graphics that move are called sprites. PICO-8 uses an 8x8 pixel sprite system. But if you start counting some of the pixels on these fish designs, they actually break that grid. For some of the fish I had to combine two sprites or more together. As a game designer I'm always thinking within multiples of eight.

The feeling I was getting when making this game, when giving life to the sprites, was just like being in the doctor's office waiting room. That's the most experience I have with fish tanks because we never had one; I never lived anywhere with a fish tank. So to me, seeing the fish mill about [in this game] is mixed with these feelings of waiting for a kind of unpleasant experience.

Mike: We had a fish tank growing up, and I do remember just staring at it--this was pre-internet so you didn't have a lot of things to stare at. So, we would stare at our fish tank.

... We were talking about paintings. I actually do think of my sculptures more as painting than sculpture. All of them have one side; there's really no dimensions [to them], they’re just flat.

They're kind of these shaped canvases.

COLLABORATION

Tiana: So Mike or Tom, I'm curious if through the process of collaborating, you rethought or questioned, what a game actually is or isn't. When I was going through the pond, I started thinking just more about that--what is the idea of a game? I felt like I could let a lot of the games just run--it's not like the boss of the game would all of the sudden kill me or make me restart at some point. It made me rethink what kind of worlds games exist in, and what that means in a physical or digital space.

Tom: As a game designer, I think about how I can create the most fun experience in a game, or impress someone with this game or create an enjoyable 30 minutes in a person's life. I think

especially at the beginning I kept wanting to add [things]. The turtle stack game has a score, but in all the other [games] we took out the idea of a score. And the turtle game is also the only one where you can kind of lose--but even then there are no stakes--it just restarts.

I think we kept each other from going towards aspects that felt too much like we were trying to “accomplish” something, because we wanted that feeling of being at the park or at the pond.

When I think of games, I'm really thinking of the experience that the person playing it is going to be having. And so in that regard, [building these games] was the same thing. We were just wanting a different experience than you might normally shoot for--which is excitement, or challenge. We were looking for more of a contemplative experience, and that’s what we designed toward. [I had to] move the target that I was aiming at (as a game programmer and designer) to a different place. You know, video game designers are always trying to add what's called “juice,” which is basically, screen shakes or sparks--you're trying to give as much bang for buck for any interaction that players have. That's called juicing up the game. Mike was really good at helping me pull all those things out and cut down to the most minimal way that we could achieve that [contemplative] feeling for whoever's experiencing the work.

.

Mike: We got carried away a couple times, I found a text where I was trying to talk you [Tom] into making an actual egg--I was thinking of the idea of an Easter egg game, where [the egg appears] in a big flash, then just drains water and then you're left with a halfpipe and there's a fish skateboarding. That was a crazy one.

Tom: It is interesting to think about the minimal amount of elements that you can put into a game and still achieve [its goal]. Hearing you guys talk about what you felt [while playing these games] is so interesting--because in the screens we're looking at there aren’t that many elements, but they’re still evoking something. That's interesting to me because usually I'm thinking about how much can I add [to a game] to evoke a feeling, and it almost starts to feel like overkill. It's good to realize that I can--

Mike: --get it down to its essence.

Tom: Yeah, cut the fat.

Tiana: Well that makes a lot of sense with the very idea of pixels and their reduction. We can tell that [these pixels] make a duck--but that's not the actual shape of a [duck’s] bill; that's not what a feather looks like. And the image that you drew of the pond itself--we can tell the difference between a pine tree form and a flower form, and a lily pad, and yet [the image] is just squares linked together.

Tom: One thing I've noticed with creating pixel art of my own, and working on this project is that often one square is meant to represent a lot of different things, and it really comes down to

[perception]. We separate the image so it’s many degrees from reality. [The image] looks nothing like a duck, but it’s almost like the icon of a duck. It suggests the idea of a duck, and then your mind works back down the chain, assigning meaning to the 17 pixels there.

Ron: I really like how this discussion in particular brings up ideas of play, and how it feels like, designing a game or making a game is also a form of a game.You have limitations and rules that you have to operate in; you have an objective you're working towards. And you're building towards that [objective], and there are dead ends and you might have to go back to your starting point. …[When an artist] makes a piece, you start to figure out how that piece is going to enter the world. You have to figure out what this is going to mean to other people--what kind of experience you want people to have [with the work]. There's a very similar kind of concern [in game design] I guess, about this relationship between your work and how it gets received or interacted with.

Sarah: talking with Tom as we were discussing this collaboration: he’s [said] “I don't feel like I'm an artist at all. Why is my name on this? I'm not an artist, I'm just like a vehicle to make Mike’s dreams come true.” Which brings me to this funny text from you, Mike.

You said: ”I started with Pond Dreams [for the title] and Electric Ducks and changed it a few times. This one makes more sense. I had [the phrase] Pixel Pond before I went to sleep and Dream Arcade was my first thought in the morning.” So this [show] really was like something you dreamt. I feel like all of these lines are blurred in a nice way between art and games and dreams in reality--Mike's having the dreams, and the little figures [he and Tom built] are like the dreams of your actual sculptures, and that play on realities really speaks well to this medium, and to the park itself.

Mike: Tom’s an artist, I don’t know what he’s talking about. I was already following you, [Tom,] and I really felt a connection between the things that we were doing conceptually and visually...right away we were on the same page early on.

Tom: Luckily there are these touchstones for retro video games and video game culture and whatever you want to call it, where you can you can [imply] a lot by saying, I want this to be Atari-like or NES, or I want this to be 8-bit or 16-bit or 32-bit... There are these demarcations in the evolution of video game technology that function almost like art movements, but they were limited, not by a collective agreement of making [things in a particular] style, but by the

limitations of how far you could push these primitive computers [at the time].

Art: Mike you mentioned that you had an image of the game[s] in your head.

Mike: And Tom created it. Exactly. It was amazing. [He] took my mind and put it right there [on the screen]. It's fantastic.

Art: I'm trying to think if that's ever happened to me--where a painting in my head, or anything that I want to make ever turned out exactly the way I wanted it to. It seems like the limitations [of the games] we've been talking about...make for easy translation.

Tom: you can’t get stuck in the details when there's no details.

Art: Maybe our brains work best at 8-bit

Tom: our optimal processing structure.

…

Mike: I teach a 3D design class sometimes and one of the final projects is to create a game that's like a three dimensional object game. I think the games that are the most interesting are ones where you have to, instead of competing with someone, cooperate with them. In a way, making these games [with Tom] was a game. We were going back and forth, talking about possible or different ideas and bringing [them] together. And the games themselves [are] not competitive. We have too much of that, we're competing with everyone that's around us, when [in reality] we get so much further when we cooperate and work together.

Tom: When we were sending texts, it was almost like a game of Pong--I would [suggest] something and then the ball would be in your court, and a week might pass and then you’d hit the ball back and [suggest something]. Days would pass and then [the ball would] come back to me. but it didn't feel like we were trying to compete. It wasn't like a game of Pong where we were trying to beat one another. Maybe it was more like a hacky sack game--we were just trying to keep [the discussion] in the air.

ENTER THE

EXHIBITION

RETURN TO

THE BOARD