RETURN TO

THE BOARD

ENTER THE

EXHIBITION

EXPLORING PLANT DAMAGE

A CONVERSATION WITH AMBER PECK

Edited Transcript

September 2, 2021

Aloe: Amber, thanks for joining us to talk a little bit more about your work! We’d love to hear more about your path to this project and your process.

Amber: I didn't really start doing art until later in life. My husband actually went to school for Graphic Design and studied visual art, but I had never taken art classes growing up. I didn't really know I liked visual art until after I had four kids. Then I made the decision to go back to school, and I mainly wanted to pursue portrait photography, do the Utah portrait photographer thing, photograph weddings, all that stuff. But somewhere along the way, I made a series of self portraits. It was about my experience with depression--trying to make a visual representation of the way that I'd felt for so many years. The way that my peers responded to it--they were touched by it and could identify with it--that was the turning point for me. I really wanted to make personal work that could touch people and I wanted to be an artist.

So I got my bachelor's degree, and right after that we went to New York City--me and my six-person family. We got a three-bedroom apartment in Brooklyn, and I got my MFA from Pratt. I graduated last October.

Sarah: Amazing. Thanks for sharing.

Aloe: Would you say that most of your work starts with a photographic base? Do you start your process photographically and then branch out, or does photography end up working into everything that you start making?

Amber: This project is different from anything I've ever done. I would give the credit for that to the pandemic. As a photographer, for me it's not just about the image, it's about the printed photograph itself. So, I'm very interested in the paper and the way that ink operates, sometimes layering ink, sometimes layering paper. I'm a very tactile photographer. When the pandemic came and I had no access to printing facilities, that flipped my work on its head. And generally my work is based on images of myself and of my children. But when I was locked down in my apartment with my children, I really had no desire to photograph them. I did a series of self portraits of me when they were asleep, but in general, my interest in things completely shifted.

One of the last two classes I took as part of my Masters program was “Art in the time of Pandemic.” It was a class where we talked about the events of the day--the Black Lives Matter protests, the election (all the junk going on), and of course the pandemic. It was a very emotional class; we were all very vulnerable. I was focused on the transition I was going to be making from New York to Utah. I did some writing [and photographs] about that, and it became this digital piece. I'd never done something that wasn't intended to be printed, so it was different in many ways [compared to my previous work]. I'd always written, but I'd never really incorporated a full-on piece of writing in a project. You guys are seeing a total shift in my work, which is fun.

Aloe: That's really exciting. So, in this project you have these images of your plant, you have this text that kind of dances over these images, and then you have voices. Before we get into that, I would love to know a little bit about your plant’s journey [from New York to Utah]; that's a huge trip.

Amber: Plants are a commodity in the city, and if you find one that's dying on the sidewalk, you take it. It had no leaves, no anything when we took it in--and then immediately the pandemic started. I think a lot of people really worked on their plants, or on their bread-making skills, or whatever got them through being stuck in their houses; part of mine was really researching how to keep this plant alive, how to deal with fungus gnats. [The plant] really meant a lot to me. One of our dogs had just died that same month, so it might have been a transference of affection towards this plant a little bit.

So I really nurtured [the plant] and brought it back to life, and got a lot of joy from it thriving during this really crappy time. When we were preparing to move back to Utah, I [realized] I couldn’t leave it. As part of our class, I wrote a letter to my plant that asked: how can I possibly leave you behind or give you to someone else? And it's not a small plant. We were cramming all of our stuff that we could into a rented vehicle, all six of us and our one remaining dog, and this plant basically sat between my legs in the passenger seat the whole 36 hours home.

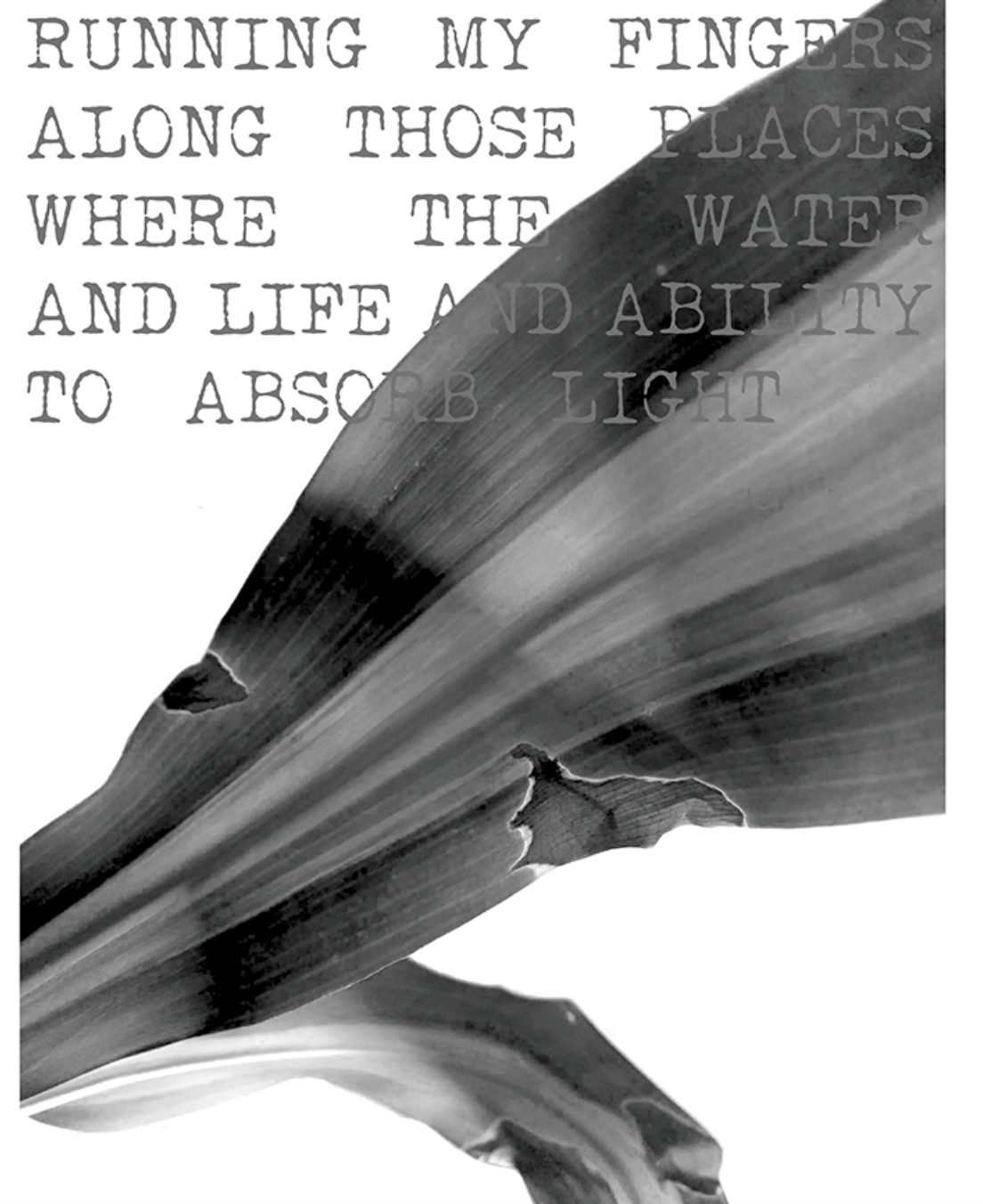

At one point we stopped to stay in a hotel. And we slept-in the next day; the plant stayed in the car and it basically got fried by the sunlight. I just felt so guilty that I'd hurt this plant. So I had an umbrella over [the plant] the rest of the way home and really tried to help it, but that damage couldn't be undone. As I was processing my feelings, I really identified with this loss and this damage and these scars on the plant. I still have it now, and those spots are still there, forever. The plant is alive, but it has wounds carved out of it.

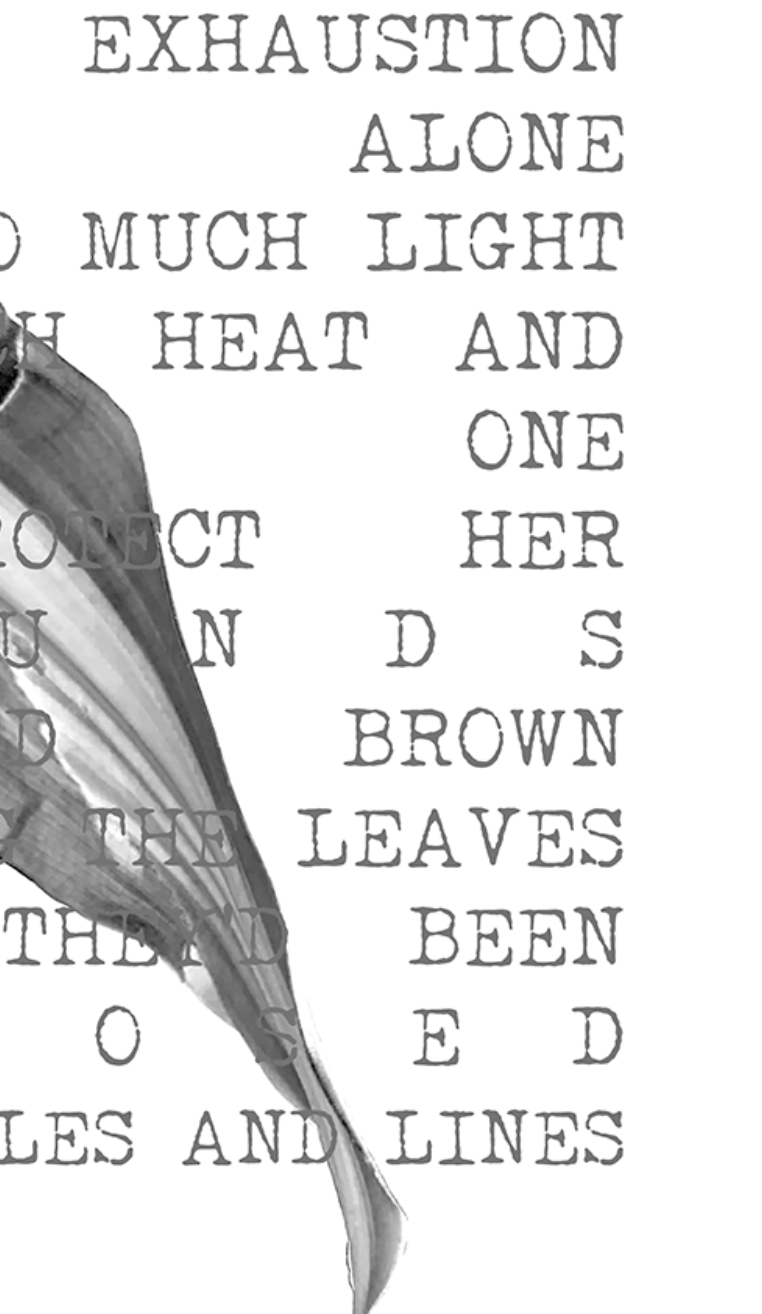

I photographed it because there were all these interesting shapes that got burned into the leaves, as well as this shift between a leaf that's full of water and life versus the very thin, almost transparent parts where the life has gone out of [the leaves]. I turned it into a black and white piece because the color was detracting from what I wanted to focus on. The black and white really made the line and the gesture more pronounced.

Ron: I'd like to hear how you thought about the negative space [in the artwork]. That felt really important to me as I was looking at the work for the first time: this marker of loss or emptiness around the plant. It's been totally removed from its [original] context. How did you think about that as you were working on it?

Amber: The images were taken in my parents’ home and there was carpet, the ceiling, and other things around [the plant], but I really just wanted to focus on and emphasize the delicacy of the leaves. I pictured [the project] in my mind as if it might be a physical book, and I liked the idea of having three segments and having the text move frame to frame as if [someone was] turning the pages. I arranged the images in different ways to see what felt right or spoke to me, and then used the text to really fill up the square. I've dabbled a little bit with text in my previous pieces, and like it to be not completely legible. [In this piece] you can see the image at one point, or can see the text at another. The grey [font color] that I chose is less visible when images are layered. It makes the work just a little less clear and less didactic. You [as the viewer] have to search a little more.

Aloe: I would love to know more about how you sorted through this idea for the voices in this piece, this idea of multiple readings and multiple layers.

Amber: Initially it was just going to be a silent piece. I think it was a suggestion from one of my mentors--she said it would be interesting if I read it out loud. I reached out to some of my classmates and asked if they’d be willing to read it for me. I didn't know what I would do with these recordings at first. I think my initial idea was to pick different phrases from each person and kind of piece them together. As I started playing the recordings, I would play several of them at the same time and get chaos, an increase in volume and in the intensity in the words. Then when it was just one person, it [echoed] the more quiet pain of that time for me. It really just meant so much. Each of those recordings has become so precious to me--to hear these people that mean a lot to me and that are still in New York and that I don't get to be with--having those voices reading the words with the shared experience that we had. They weren’t identical experiences, but so many of the people in New York left the city to go live with their parents like we did, or lost their studios, or went through a lot of change. It has meant a lot to me to have those voices in that shared experience and feel connected to them, even though COVID took away my ability to physically be with them.

I really appreciate the format [of the park]. When I made this piece I really didn't know if anyone would ever see it because I didn't know in what way I would present it. This format was really ideal for me.

Aloe: I really like this feeling of echoes coming through time or space. To me it really does fit in with this mood of this pandemic, where we're all kind of virtually throwing our voices out there. We haven't had that possibility to be in person and so there's been this assumed void. That's really implicit in your piece--which I think would stand out regardless of the pandemic--but it does start to bear on everything. This kind of negative space, this open space where the words and voices are reaching through that negative space and maybe even being the hands that tend to that plant, is really beautiful.

Ron: I also really appreciate how you've set up the voices with this. You're giving the viewer control over how they want to experience it, whether as multiple voices or one voice. It feels a lot like an experience that you might have personally with a book. You’ve talked about it as a book, and it feels very much like a book, but then it’s in this digital space. [Viewers] are able to take some of that control back with how they can interact with the voices. I think it’s a really clever way to be in that “book” space, but have it translated into a communal online experience.

Amber: When I was initially playing with the pacing of the [text] it was so hard to decide how fast any individual person would read it. I slowed it down and had pauses when the words would disappear and you would just see the image, and then another page would appear; but I felt really insecure about making someone sit there with my words for longer than they would want to. Giving control of the voices [to the viewer] alleviates that [struggle] for me. I'm not forcing someone to sit there and read my words for longer than they want to. This is a new experience for me, saying, ‘Here, pay attention to this very vulnerable poem that I’ve written.’ I like giving some control to the audience.

Ron: it is a very vulnerable space when you start writing as an artist. I went through that in grad school, and it did feel like I was making a lot of people have to sit with me for that. It's a brave thing.

Amber: I like to think that now there's less of a facade of the cold unsharing artist that just says, ‘Oh well, you read into my image whatever there is.’ I feel like it's more acceptable [to share] now, and this comes from more female artists being celebrated. You can share your personal story, and make vulnerable work, and not have this wall between the artist and the viewer. That's definitely how my work is.

Art: As I listen to you describe this Amber, I'm thinking of one of your books that I've seen in person, a physical book. It was like a fairly big book, more than a foot wide and it didn't read very linearly. I don't recall text, just photographs. The photos were very dark and had a lot of ink on the page; the paper was actually filled with an overabundance of ink. I'm trying to remember the image--an image of you--it was very dark and hard to make out at times, but it was you holding up a ceiling, right?

Amber: I was standing on my kitchen table in my apartment and pushing towards the ceiling and standing on my tiptoes, trying to get out of that space.

Art: Yeah. And I remember that sense of you pushing the ceiling, standing on your tiptoes. It was a really vulnerable gesture. And I definitely recall that kind of claustrophobic feel in the reading of that book.

What is your relationship to the audience? You're obviously putting yourself out there, in very open and sentimental ways. What is your hope, when the audience engages with your work?

Amber: My transition into art was really my beginning of going back to school. There is this invisibility that I felt as a mother of young kids, just feeling that nobody saw me, nobody heard me. Kids don't listen to you, especially little kids. They only tell you when you suck, basically. I needed a voice, and I needed to be seen. When I made [my first] series of self portraits and somebody said, ‘Oh my gosh, that's how I feel when I'm [experiencing] my mental illness,’ that was just so empowering to me. My voice touched somebody else and made them feel understood and seen. That's really been my path forward. I'm going to share the chaos of children, how I sometimes resent this role [of mother] that I have, and that I sometimes want to run away. If I share that feeling and somebody else identifies with it, that's my ultimate goal as an artist. Sometimes it feels like I'm just speaking to the stay-at-home moms that feel the way I do, but I also feel like everyone has a family, everyone has those complicated push-and-pull relationships between their parents or their siblings.

Sarah: I have been changing a poopy diaper while you're talking, and I feel seen.

Amber: My kids have gotten used to [my work]. They know that parenting isn't all good, parenting is complicated. They know that I suffer from depression. I hope that by being open with these things, I will hopefully touch somebody. That's my goal.

Sarah: I think that's really beautiful and obviously I, as a stay-at-home mom, really personally relate, and also as a person who has several mental health challenges. I'm developing this body of work right now in which I dive into my mental health, and I'm realizing that even though I've spent years trying to destigmatize it for myself, there are still walls like that everyone has to break through. I think it's really beautiful that you found this path where you feel comfortable in your vulnerability. I feel like you're very poetically sharing something that's deeply personal for you, but is also universally relatable. Even though I will never know your personal experience, I see your work and I feel that weight, and it brings me into that sphere in a really palpable way.

Amber: I’ve never wanted to speak for all mothers or everyone with depression; I'm just sharing my personal experience. Hopefully it connects with somebody.

Art: One of the things that we focus on at PARC Park is Utah's relationship to the art world and Utah artists’ relationships to the greater art world discourse. How do you feel like your work is received and viewed by an audience here, compared to the audience you had in New York?

Amber: When I was applying to grad schools, I was really worried that making work about motherhood, making really personal open work wasn't going to resonate with the professional artists that were looking over resumes and portfolios. But I got a great reception from these people that I respected at the schools, and I think that's because of the universality of family relationships.

When I was at Pratt, we had visiting artists come and have studio visits. My studio really became like a therapist’s office. People would share their experiences with their kids, they would share their experiences with mental illness, sometimes we would have crying conversations in my studio. I really felt like the work I was making was connecting with people of all kinds. It was connecting with fathers, it was connecting with people that could see the darker side of childhood. I learned by leaving Utah that my content wasn't only relevant to Utah.

In New York people are very much who they are--you don't pretend you're happy. You cry openly on the subway when having a bad day. I felt so connected to that, and it's been difficult being back in Utah, where there's a culture of keeping our own crap and struggles to ourselves. And that doesn't help anyone. It makes us think that we're all alone in our struggles. I would really like to kind of be an example of [that vulnerability]. My dirty laundry is just out there, my weaknesses are out there. This is who I am and I'm not gonna pretend to be something else.

Sarah: I've had that experience in different places I've lived and traveled as well, and I think that getting rid of that pretense is really beautiful. I'm sure that all of us can relate with that feeling right now, especially with the pandemic.

You're making this work that's meant to be viewed online, and it's really easy to curate our lives online right now. [Your work] is really necessary here and in our culture. A lot of the art that people want to consume here in Utah is very clean and picturesque and easily palatable. It's nice to see people kind of pushing against what might be more readily available or accepted around here.

Amber: I mean, this piece definitely isn't messy aesthetically. It's very clean and organized. It’s me sharing these messy feelings in a sterilized sort of environment.

Ron: I think the way social media is starting to function or starting to lean towards functioning now, is beginning to acknowledge these imperfections in our live streaming and acknowledge the reality [of life]. But it's still hard to escape some of the commodification that comes with that sharing. It’s becoming a trend and it's fashionable to show off. When looking at this piece, I don't feel the [visual] messiness that we've been talking about, as you were saying, but I do feel a realness there. It doesn't feel like it's being set up to disguise anything else.

Amber: I think the pandemic helped with people really looking at their mental health. That kind of universal suffering at different levels helped people to really be more genuine or realistic about the things we can achieve as human beings, and what our limits are.

Aloe: what effect do you think this pandemic experience and this new work will have on your future projects?

I'm not sure what I'll be working on, going forward. I'm still very interested in physical objects and making physical books that people will hopefully touch again. I don't know what my digital path [might be]. So I don't know where I’ll be in the future. This project still feels like a “one off” for me, and we'll see if I do more in the future. I'm very, very connected to showing faces and limbs and hands. It was only by personifying this plant and really connecting with it in a personal way that I think it became content that I could identify with. I don't know if any other inanimate objects are in my future, but we'll see.

Aloe: It's been so good to hear more about this work and to get into some of the details with you!

Sarah: We really appreciate you taking the time to talk with us. And thank you for taking a risk to make something new, and being part of PARC Park!

Art: It’s been great talking to you, thanks Amber.